That day started like any other on the ice. I was on my second season on the ice, running my third trip up the ice in 2013. The weather had been strange that year. Temperatures in the north warmed up―the previous day, the sun was out, and the roads which crossed the portages began to glaze with a slick coating of ice.

We launched that day in darkness, departing the city of Yellowknife, our Super B’s loaded up with fuel, bound for the Ekati Diamond Mine. By the time we were up the Ingraham trail and onto the ice, an overcast sky hung above, its canvas flat opaque. Our convoy of three consisted of Brad Hardy, myself, and Gerald Keefe. Brad was in the lead, me in the middle, and Gerald was our tail gunner. As with every trip, I shot plenty of pictures. We talked for hours on the radio as we made our way across lakes and portages that would get us to our halfway point. Lockhart Lake. Talking, debating, and joking around on the VHF radio is what drivers do to stay ahead of the fatigue. A run to Ekati could take as long as 18 hours, and once you’ve committed, there’s not a lot of places to stop and sleep. So, it was a typical day. We were all in good humor that morning. As this was my second season, I was well acquainted with Gerald and considered him a friend. I had no idea that he would be there beside me when all hell broke loose.

We were coming off Gordon Lake when Brad called, “Three north on 20,” to alert southbound convoys of our presence. In some spots, it can be tight meeting a southbound truck. A small pond only separates portages 20 and 21, no more than 30 feet across. It isn’t a great spot to meet another rig, but it happens, and drivers adapt. Coming down the hill onto the pond is a feat in itself. You go straight down a hill, pushed by your twin tankers. Once you’re on the pond, you have to turn the rig in a hard right to climb the icy grade to portage 21.

I was on portage 20 now when I heard Brad call, “Three north on 21!” There was a pause. I was halfway across the portage when Brad called back, “Mark, get your foot into on twenty-one. I was wiping my feet all the way up that one.” Which meant he was losing traction. I readied myself for the next pond, feeling confident, wide awake. I’d done this pond crossing north, and south over fifty times, so I adjusted for conditions.

I came off portage 20 and got onto the pond with no issues, But when I started into the last part of the turn that would take me up onto Portage 21, the steer wheels lost their grip on the road and became skis. Instead of propelling up the hill, I was in a direct line with the bush. I tried to bring it back under control, but the tankers of fuel had power now. Next, I was crashing into the woods, small trees falling victim to my moose bumper. There was a thud, and as violent as the crash felt, it was over in mere seconds. I looked in my passenger window at the mirror and saw my pup was blocking the road. Gerald was coming, only half a kilometer behind me, probably more like two hundred meters by then.

Grabbing the radio, I called, “Everyone stop! I’m off the road at 21!” Then I was getting my winter gear on. Behind me, Gerald got word just in time. He got onto the brakes as he was coming off portage 20. With my arctic gear on, I got out to assess the damage. That was when my heart ended up in my throat. The driver-side fuel tank had struck a rock and been ripped open. I scrambled through the snow and under the lead tanker to grab my pails. Gerald was out of his truck.

“My fuel tank’s ripped open. Bring all your buckets!”

Then I climbed back under the trailer with three buckets in my hand. When I got up to the side of the truck, I couldn’t get the pail underneath the ruptured tank, so I jammed my arm underneath between the laceration and the rock it sat on and used it as a conduit to drain it into the pails. Gerald showed up with all his buckets and slipped on the same rock that had ripped open my fuel tank. He fell on top of me and then thanked me for saving his life. Twice.

“Huh?” I was kneeling in the snow, my right parka arm jammed in a crevice of rock and steel, acting like a candle wick directing fuel into a container instead of onto the ground. I didn’t understand what he meant.

Gerald pointed to the rock. He would have hit his head if I hadn’t broken his fall, and then he said, “I would run right into you. If you hadn’t called out, I would have hit you for sure.”

I looked at him and said, “You can buy me a beer when this is over.”

Gerald laughed. So did I, even though I felt like someone just fed my ego into a shredder. The damage to the truck weighed heavy on me. I was questioning what I could have done differently, and meanwhile? I was soaked in diesel fuel, pumped on adrenaline.

Security showed up, and when he got out of his pickup, he fell flat on his back. He picked himself up and walked like a drunkard wearing roller skates. He came down, “You guys need anything?”

“Something to put the fuel in,” I said, and as if by a miracle, a guy appeared with an empty 45-gallon drum and brought it down to us. Roughly a half-hour after the crash. I used a compound called Plug & Dyke, a powder that turns into putty and can work miracles on a punctured fuel tank, to seal the lacerations in the tank. You only have a few minutes to work with the stuff, but I managed to plug the holes and stop the remaining fuel from leaking out. Part of that dyke involved a tree branch that had pierced the aluminum fuel tank.

As I climbed back up onto the road with Gerald, the security commended both of us for containing what could have been a disastrous spill. I asked him, “You writing me up for this?”

“No, the road’s a skating rink. It was an accident,” he said and added, “I have to commend you, boys. You averted an environmental mess.”

“It’s what we do,” I said. That wasn’t arrogance―it’s bred into a fuel hauler―you don’t want to spill a drop. We train for it constantly. His words should have made me feel better, but they didn’t. In the distance, I could hear the recovery boys coming to pull me out. Generally, they will not pull tankers backward for fear of causing significant damage, including rollover and spill. When they got there, I signed a declaration of responsibility for all damage incurred during the recovery, be it mechanical or environmental.

Putting my signature on the document made me feel even better.

It took three winch tractors and four hours to pull me off that rock without destroying the undercarriage of that W900. When it was done, my wounded rig and trailer were dragged up to the sugar shack. An oxymoron because you found quite the opposite of sweetness in that in the sugar shack. It was, for lack of a better word, a shit house.

“The road is open!” Security called, and the convoys began rolling north and south, packs of four twenty minutes between each. Each passing, taking in the battered spectacle of my rig. With the road cleared and my rig waiting for recovery, it was time for my friends had to leave. Gerald and Brad returned to their trucks and started heading north. I was on my own at this point. I felt the sting to my ego as gawkers drove by taking in the truck that had hung them up for hours.

I ended up jumping into a pickup with the 2IC of Nuna Road Maintenance out of Dome Lake. Nuna had sent the three winch tractors to recovery me. It was their job to maintain and keep the road open. Word came that Big Red, driven by Curtis, our winch truck operator for Ventures West, was on his way with a replacement rig for me and to take my battered W900 south to Yellowknife for repair.

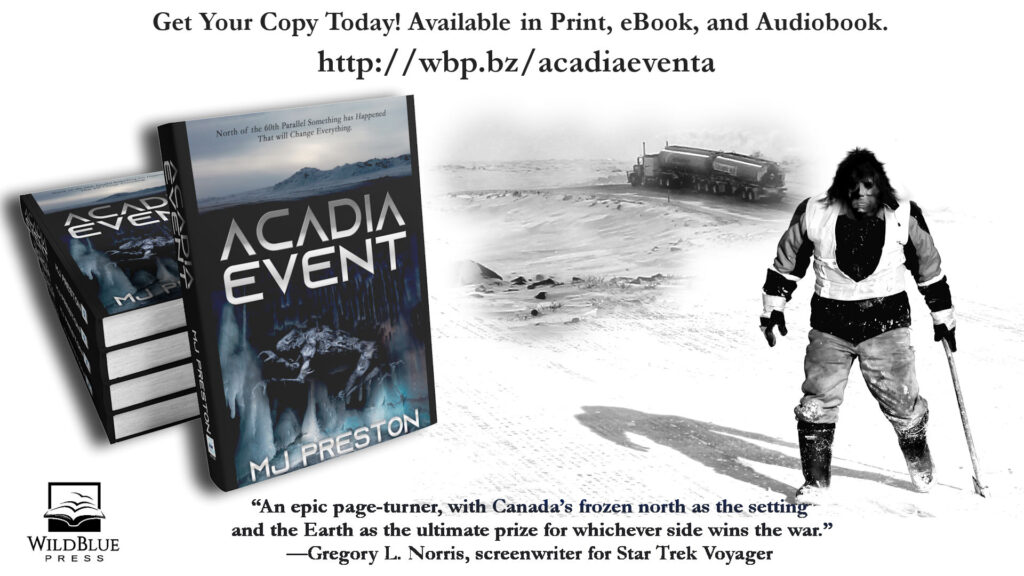

GRAB A COPY OF MJ PRESTON’S NORTHERN SYFY-HORROR ACADIA EVENT

“Stop!” A diver called. I’m spun out on twenty-two,” A driver called, and the road was again closed. We drove to the scene, where I jumped out, helped the driver chain up, and took about fifteen minutes to get him rolling again.

“The road is open!” The 2IC of Nuna announced on the VHF radio, and trucks began again. Then two more reports of spin-outs came across the wire. “The road is closed.” We darted across the portages, and I helped out two more drivers get their chains on while heavy equipment pulled them up the grades. Over the next ten hours, the road would reopen and close over a dozen times as calls for assistance came from drivers losing traction. I chained up seventeen out of the eighteen trucks that sent out distress calls.

After midnight, a Kenworth pulling super b’s jackknifed on a portage, and I found myself assisting with that recovery. That was the final recovery of the day. On Gordon, Lake trucks had been circling for hours because they could fit on the portage. I heard one driver say, as they circled for what must have been the hundredth time, “Here we go again. I’m living in Nascar hell.”

The entire day had been surreal. I was exhausted, I smelled of diesel, and I would be getting a shower until my replacement rig arrived. That happened around 3 AM when an exhausted Curtis showed up at the Sugar Shack with the flatbed and a replacement rig. The Kenworth was running, so I went back to my truck, stripped out of my gear, and put clean clothes on. It was better, but I needed a shower which wouldn’t be forthcoming until I reached Lockhart Lake. We decided to grab at least four hours of sleep before switching the tractors. I climbed up onto Big Red’s flat deck and into the idling Kenworth, where I collapsed from exhaustion.

The following day the sun came out, and Curtis and I pulled my new wheels off and then put the W900 on his deck. That done, we chained it down, and Curtis was gone south. Now all I had to do was wait. Eventually, I tagged onto a northbound convoy, and we went onto Lockhart Lake. When I came in, there were looks from other drivers who knew. Some guys came up and chatted, tried to be supportive. Many looked with the interest of a rubber-necker.

I carried on up the road, and by the time I got back from the Ekati Diamond, the boys in the shop had my W900 rigged up with a new fuel tank, and I was back in the game.

I reflected on what happened that on the ice. It’s something every driver does after an accident or an incident. The melting of the road and the dusting of snow made it a skating rink, but I will always wonder if something I could have done differently. Maybe if I turned a little wider? Perhaps if I hadn’t been so aggressive to get up that icy grade? Maybe?

Now, I look back, and though it was an unpleasant experience, it was also a chapter in the story of my ice trucking days. One I will remember for all my days. One I would never want to repeat. I can’t remember if Gerald bought me that beer for saving his life twice, but I’ll never forget how he was there by my side on that day from hell on the ice.

Thanks for listening.

MJ